Okay, okay. I cannot take full credit for that title either.

Jill R. Ehnenn opens her article up situating the reader into a queer reading of J.K. Rowling's pinnacle series. By inscribing new meaning onto one of pop culture's most pivotal characters, Harry Potter, we instantly begin to see our favorite wizard in a brand new light. Framing Harry Potter as looking like a lesbian, Ehnenn offers up the queer liminality that Harry Potter offers to its readers. Beyond a reading that analyzes the fantastical elements of the series, Ehnenn approaches the series from a unique lens. She chooses to find certain distinctions between fantasy text and queer text and find parallels between the two. But more than how the series functions as a non-normative reading of the queer identity, she offers up something a little extra-- she tells us precisely why the series is a crucial reading of queer politics.

In a way, we all know what it is like to be different. At times, we feel like we are on the outside, isolated, so far removed from our realities that we need to escape. On a surface level, Harry Potter works as an identity marker for so many of us who have felt like we do not belong. The stories are fantastic, whimsical, and empowering. But if we look beyond it as a mere form of escapism, we can also see that however fictional Harry Potter's adventures may be, in a way, we can all relate in some capacity. Ehnenn details that this may be especially important for queer youth and queer readers. I mean, let's think about it here for a second: Harry Potter begins his life living in a closet under the stairs. Why did I not draw that correlation before?? Ehnenn explains that in the world of Muggles v. Wizards, Harry is the queer, unspoken for identity. When we first meet him in the series, we know that he is bound to do great things-- the series is his name, after all. But living with the Dursley's, we see that he is shamed for his wizarding pedigree. But then he arrives to Hogwarts, and we find that there is no longer shame for who he is. There is pride. There is humility. And there is acceptance. But note! The series does not follow Harry's journey to popularity! Rather, it is about finding that acceptance from true friends.

I know. That may sound corny. But when you get down to it, an analysis such as one that Ehnenn offers was not only inevitable, but it must be read as valued. I know plenty of people who have denounced Harry Potter as a work of the devil-- teaching kids and adults to study witchcraft. That's satan at work right here, folks. Yet, for those who love the series and believe in its ability to empower, there is something so much stronger at work here. In regarding the impact of the series, far after the last page has been read, Ehnenn explains, "They [the Harry Potter books] begin to denaturalize hegemonic ways of perceiving identity and identity categories" (p. 241).

Indeed, Ehnenn concludes her article by insinuating that it is not enough to just sit around and say, "Hmmmm I think Harry Potter is a lesbian" or that there is homoerotic subtext between Harry and Ron (although that is pretty fun) or even that there is weird sexual tension between Hermione and Professor McGonagall. All of these are amusing and could potentially be read in that way. And don't even get me started on how we could view Dumbledore, and Rowling retroactively outing him after the series concluded. Instead, Ehnenn points to the idea that queer texts exceed beyond what makes them different from normative texts. Rather, we should be asking how and why such readings are important. Is it perhaps they empower the reader to think differently? And if so, how? And why do we need such readings. What can they tell us about dominant ideologies. And I leave you with this: think to your favorite book. It may be Harry Potter, it may be something else entirely. Regardless, challenge what you think you have know about that book-- read it again. And read it with a fresh perspective. Don't be afraid to jump right in once more into that world-- and find what makes it queer.

Thursday, September 22, 2016

Saturday, September 17, 2016

All My (Queer) Children, or; A Title I Cannot Take Credit for

I'm going to level with you all: I don't watch soap operas. I know they are spoofed, I know they are dramatic, and I know that there are plenty out there. Don't get me wrong, I DO know all about Susan Lucci's Emmy dry spell. But otherwise, I am up a creek without a paddle.

Color me surprised, however, when I started my reading for the week.

Cathy Leaker tackles a difficult subject-- queer representation on soap operas. In particular, she examines All My Children's first notable lesbian character, Bianca Montgomery. What makes this character's trajectory so fascinating is her limited queer experience on the series. Why is this, you may be asking yourself? As Leaker explains, the soap industry (not the bubbly kind) has had a long, tumultuous relationship when it comes to gays and lesbians on their shows. And yes, while Bianca was a lesbian who lasted on the show for almost five years, Leaker also notes how understated this representation is.

And most importantly and equally as damning, Bianca appears to be punished for identifying as a lesbian on the series. I guess you could call Bianca "unlucky in love," because her relationships always last until a certain point and then fizzle away. She falls in love with straight woman, they do not love her back. It is all tragic. But wait! Not all is lost for Bianca! For instance, Leaker points out that after finally finding herself in a relationship with bisexual, Russian spy Lena (don't ask) and America witnessing one of the first same-sex kisses on daytime soaps, Bianca is promptly raped and impregnated by Lena's ex-boyfriend. And then she is pushed off a balcony and lands in a coma. But fret not, all! She is then written off the show with her child and one ambiguous relationship with a woman, as she chooses to travel to Paris-- an apparent lesbian haven, according to Leaker.

I know. Doesn't that make you want to start watching soap operas? See, when I said I knew that soaps were dramatic, I was not expecting it to that level. Nor was I expecting all of it to be just be added onto Bianca's character sentence. And just think: how are we, the audience, supposed to take this? I'm uninformed when it comes to this subject area (i.e. soaps), but what I do know is that representations such as Bianca's are disconcerting. How do they communicate to the LGBTQ+ community? What does this say?

Perhaps we will never know. Which is sad, in a way. Soap operas are pervasive, they are clearly not going anywhere in the canon of television. But where are we to go with portrayals such as these?

Color me surprised, however, when I started my reading for the week.

Cathy Leaker tackles a difficult subject-- queer representation on soap operas. In particular, she examines All My Children's first notable lesbian character, Bianca Montgomery. What makes this character's trajectory so fascinating is her limited queer experience on the series. Why is this, you may be asking yourself? As Leaker explains, the soap industry (not the bubbly kind) has had a long, tumultuous relationship when it comes to gays and lesbians on their shows. And yes, while Bianca was a lesbian who lasted on the show for almost five years, Leaker also notes how understated this representation is.

And most importantly and equally as damning, Bianca appears to be punished for identifying as a lesbian on the series. I guess you could call Bianca "unlucky in love," because her relationships always last until a certain point and then fizzle away. She falls in love with straight woman, they do not love her back. It is all tragic. But wait! Not all is lost for Bianca! For instance, Leaker points out that after finally finding herself in a relationship with bisexual, Russian spy Lena (don't ask) and America witnessing one of the first same-sex kisses on daytime soaps, Bianca is promptly raped and impregnated by Lena's ex-boyfriend. And then she is pushed off a balcony and lands in a coma. But fret not, all! She is then written off the show with her child and one ambiguous relationship with a woman, as she chooses to travel to Paris-- an apparent lesbian haven, according to Leaker.

I know. Doesn't that make you want to start watching soap operas? See, when I said I knew that soaps were dramatic, I was not expecting it to that level. Nor was I expecting all of it to be just be added onto Bianca's character sentence. And just think: how are we, the audience, supposed to take this? I'm uninformed when it comes to this subject area (i.e. soaps), but what I do know is that representations such as Bianca's are disconcerting. How do they communicate to the LGBTQ+ community? What does this say?

Perhaps we will never know. Which is sad, in a way. Soap operas are pervasive, they are clearly not going anywhere in the canon of television. But where are we to go with portrayals such as these?

Sunday, September 11, 2016

Ugh! Do we need to talk about The Danish Girl again?

Yes. Yes, we do.

I was chatting with a friend yesterday, and she sent me a Snapchat saying that she was about to watch The Danish Girl with a group of friends. Having seen the movie last year and being an avid naysayer of Tom Hooper's film, I replied with a vulgar summation of "Good luck, friends." Shortly after, she took to texting me, asking why I disliked it as much as I did. And I jumped in.

I was chatting with a friend yesterday, and she sent me a Snapchat saying that she was about to watch The Danish Girl with a group of friends. Having seen the movie last year and being an avid naysayer of Tom Hooper's film, I replied with a vulgar summation of "Good luck, friends." Shortly after, she took to texting me, asking why I disliked it as much as I did. And I jumped in.

- The film essentializes the identity of Lili Elbe, reducing her to a stereotype

- Eddie Redmayne. Listen, everybody. I like Eddie. But here... no. He whispered far too much and he created this woman who appeared weak and vulnerable the whole time.

- Speaking of, this is not all Redmayne's fault. Where is Lili's strength? Why is she this bizarre wallflower? Why do we seem to care more about her cisgendered wife?

- That ending. Do I really need to say more? I am so relieved that Lili's struggle can be personified through a scarf. Thanks, Tom Hooper.

The list goes on and on for me. Ask me what I liked about it, and I will tell you Alicia Vikander. But if we're talkin' awards for Miss Vikander, I will say Ex Machina and promptly move on.

|

| Bless you, Alicia... and that dog |

I digress. After being asked this, my friend said that the group she watched it with completely disagreed with me and felt the exact opposite. Now I am not in the business of telling people how to think. In fact, while I can get on my high horse when it comes to what I think about movies and TV, I try to have an open mind. Who would I be if I was just spouting my opinions about the pop culture I indulge in? [insert joke about politicians and the state of the 2016 election here] But what fascinated me most was how our conversation developed into something way more fascinating than "I liked it" "Well, I didn't" and so on.

Instead, my friend asked me what I felt about Eddie Redmayne playing a male-to-female (or MTF) transgender woman. She thought that it seemed insensitive to the portrayal, but then again, who was she to have that opinion.

This got me thinking. When it comes to films, television, books... well, any type of media that we consume, where do we draw the line on our opinions? My friend, for example, stated that because she did not identify as trans, nor did she know anyone closely, could she say that the film was offensive? Could she say it was an honest portrayal? At first, I said yes. After all, the film was made for public consumption, free for critics (professional and bloggers alike) to pick apart at their earliest convenience. And hey! Carol Grant summarizes precisely why I think the film is far from progressive, and she is writing with years of experience as a trans woman.

But then I got to wondering. It is SO easy for us to sit here and critique the media we consume on a daily basis. And that's good. I think we are responsible consumers to discern what is good, bad, and ugly. But at what point do we separate ourselves from the media we take in? And more importantly, when can we take a step back and say "that's not my place to say"? I don't think we will ever come to a wholesome conclusion here.

In the case of my text conversation about The Danish Girl, it's a pity I couldn't be there in person and talk with this group extensively about the film. I want to hear what they liked about it, what they didn't like about it, and I could tell them why I found Eddie Redmayne to be as insufferable as he was. Some of my thoughts may have got lost in translation, I can never articulate myself well through texting, but to sum up: remain cognizant of the texts you indulge in, my friends. Truly think about what you are reading, watching, etc. And then don't be afraid to turn it on its head and embrace the conversation that will ensue. Trust your judgment, and jump right in.

Saturday, September 10, 2016

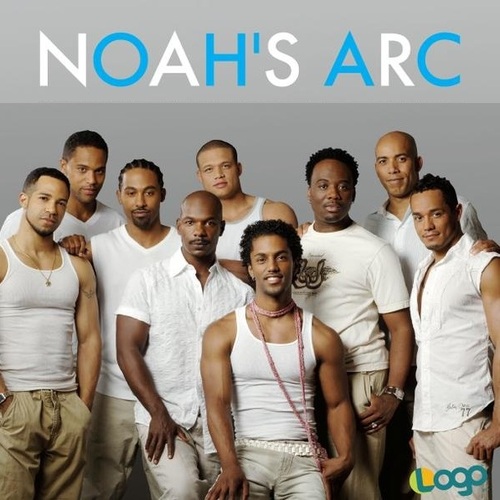

Build Me an Arc as Fast as You Can!

The reading I do for my classes are like a double-edged sword: sometimes, there's so much that I become overwhelmed. Plato + gay things = WHAT? But other times, the readings I do resonate with me, simply because I was not expecting to take away much from it.

Hence is the case for the primary reading I had this week. Pulling from Queer Popular Culture, I selected Chapter 2, "Queering/Quaring Blackness in Noah's Arc" and was pleasantly surprised. It's hard, I think, to read (and subsequently) write about shows you have never seen, and I was cautious. I chose to read this particular chapter early on because I feel that the bulk of my studies do NOT take into account the racial dimension to queer studies and I felt that I owed it to myself to expand beyond what I already knew.

Written by Gust A. Yep and John P. Elia, the article explores Noah's Arc, a series that was "dubbed as the black Queer as Folk, and the black gay Sex and the City" (p. 28), and I already knew that I was into something good here. Although I was unfamiliar with the series, I knew that I was heading into the right territory to figure it out. They begin by using the word quare quite a bit, and I was instantly confused... so much, in fact that I wrote "quare???" at the top of the page. And you may be wondering, "does this have anything to do with queer" and the answer is a hearty YES! In fact, when pinpointing the relationship between the two, they argue that to "queer" something (a text, for example), one attempts to make the familiar unfamiliar, to subvert expectations about what we have come to expect from the media we consume. On the other hand, to quare is calling attention to the whiteness that permeates throughout queer theory. Essentially, it attempts to queer... queer. To find the quareness of a text means to examine the underlying intersections between sexuality with race, class, etc. Interesting, right?

Yep and Elia dive into the series, critiquing how it quares class, gender, and sexuality. What is especially important here is to understand that they offer the lens of quare to analyze how this text, Noah's Arc, functions differently than most texts-- primarily because the series adds on race to conversations-- conversations that would be commonplace from within the cannon of queer literature. They offer individual case studies from the series, circumstances that allow the readers to really see how/why such a discussion is important. By combining the queer identity with the black identity, we are in turn deconstructing how race can be talked about through mediated texts.

Ultimately, texts that focus on the racialized body tend to center on the heterosexual male body, thus ignoring the woman or the gay black man. On the count of three, say it with me: 1... 2... 3 PROBLEMATIC. But what's even more fascinating is that, even though Noah's Arc was picked up by Logo, it was inevitably cancelled after two seasons. Logo, you guys, the GAY CHANNEL. While they do not note this anywhere in their article, it is critical to note what this says about texts that are queering what we already think of as queer. I know, it gets kind of trips after a while, but reading this article made me think critically about the texts that I tend to ignore in the first place. I'm part of the problem, this is true, but beyond that... how do we find a place for queer texts that subvert what we already think of as queer? This is certainly a question I won't be able to answer right now, or even in the coming weeks, but perhaps I can come to some conclusion near the end of the semester.

But while we're at it, I have one more query. I want to watch Noah's Arc. This article really solidified it, what with discussions surrounding HIV, class, and sexual imbalances. But... where can I watch it without paying $60+ to buy the DVD's? If you have any suggestions, let me know.

Hence is the case for the primary reading I had this week. Pulling from Queer Popular Culture, I selected Chapter 2, "Queering/Quaring Blackness in Noah's Arc" and was pleasantly surprised. It's hard, I think, to read (and subsequently) write about shows you have never seen, and I was cautious. I chose to read this particular chapter early on because I feel that the bulk of my studies do NOT take into account the racial dimension to queer studies and I felt that I owed it to myself to expand beyond what I already knew.

|

| Way to go, Logo! |

Yep and Elia dive into the series, critiquing how it quares class, gender, and sexuality. What is especially important here is to understand that they offer the lens of quare to analyze how this text, Noah's Arc, functions differently than most texts-- primarily because the series adds on race to conversations-- conversations that would be commonplace from within the cannon of queer literature. They offer individual case studies from the series, circumstances that allow the readers to really see how/why such a discussion is important. By combining the queer identity with the black identity, we are in turn deconstructing how race can be talked about through mediated texts.

Ultimately, texts that focus on the racialized body tend to center on the heterosexual male body, thus ignoring the woman or the gay black man. On the count of three, say it with me: 1... 2... 3 PROBLEMATIC. But what's even more fascinating is that, even though Noah's Arc was picked up by Logo, it was inevitably cancelled after two seasons. Logo, you guys, the GAY CHANNEL. While they do not note this anywhere in their article, it is critical to note what this says about texts that are queering what we already think of as queer. I know, it gets kind of trips after a while, but reading this article made me think critically about the texts that I tend to ignore in the first place. I'm part of the problem, this is true, but beyond that... how do we find a place for queer texts that subvert what we already think of as queer? This is certainly a question I won't be able to answer right now, or even in the coming weeks, but perhaps I can come to some conclusion near the end of the semester.

But while we're at it, I have one more query. I want to watch Noah's Arc. This article really solidified it, what with discussions surrounding HIV, class, and sexual imbalances. But... where can I watch it without paying $60+ to buy the DVD's? If you have any suggestions, let me know.

Saturday, September 3, 2016

Gay Gorillas in the Mist

I love sitcoms. I'm talking mid-late 90's situational sitcoms-- you know, those that reinforce gender stereotypes, where the laugh track is abundant, and they live in a metropolitan city because they are just like us. I'm not even trying to be facetious here; sitcoms are great. Some of the reading I did this week in regards to my independent study was focused on two sitcoms: Ellen and The Ellen Show. And no, I'm not referring to her talk-show. Nay, these shows worked side-by-side to introduce Ellen DeGeneres as a lesbian to mainstream audiences.

In her article from Queer Popular Culture, Jennifer Reed outlines the mounmental work that Ellen did for the LGBTQ+ community in regards to queer representation on television. Today in 2016, we may be asking ourselves, "what's the big deal? I see plenty of gay people on my screen ALL the time." And while that may be true to a certain degree, Reed initially argues that, "Mass media is where public life happens at this point in Western history" (p. 10). Indeed, it is easy for us to sit around, assuming that we know that we learn from what we watch, but what we fail to address at times is how largely we are influenced by our daily programming.

Reed elaborates on this further when she discusses how Ellen manages to maneuver between queer, gay, to even postgay. These differences are spaced out through the duration of Ellen's two sitcoms of Ellen and The Ellen Show. In her first series, Ellen is living the life as an asexual woman, never being able to form a connection with another man. Reed highlights plot lines that indicate how Ellen is blossoming into a gay woman, and by portraying her as such, Ellen subverts the label of straight and gay. Thus, she is in this middle ground, a queer middle where she can subvert any and all expectations of her gender performance and/or sexual preference. Of course, due to the nature of the program, these are used for laughs, but Reed argues that this was a sweet spot for Ellen and for young gays across the country. The fact that Ellen was even hinting at her sexuality through the series, as well as her appearances on talk shows, indicated a drastic transition into our consumption of queer culture on mainstream television. Basically, this was huge!

"I'm gay." Two words that brought Ellen to the forefront of popular culture. The truth came out and the world needed to be ready to accept it. After winking at the camera for almost the entire fourth series of Ellen's run, she comes out as a gay woman. How cool is that? It is! Today, we may find it commonplace, and we still are problematizing coming out narratives as privileging heterosexuals' acceptance of one's queerness. But in 1997, wow. It makes me wish I had been there to witness it. As Reed dives into what this meant for gays everywhere, she also acknowledges that the series then took on an inadvertent responsibility. She notes, "If we think of television as a teacher, the question becomes who was being taught and what" (p. 17)? Essentially, Ellen being gay was a phenomenon. Okay, great, Where do we go from here? And what precisely can we take away from that.

Well, Ellen got cancelled. And shortly after, The Ellen Show premiered. This series was about a different woman with the same first name, and while she identified as gay, Ellen explicitly stated that she did not want the happenings in this show to be that of a gay woman. She argues that there is so much more to her personally than being a lesbian. Reed mentions here, that from moving from queer to gay, Ellen was now in a postgay phase of her cultural identity. In other words, this was a movement that hit on the idea that there are numerous facets to the queer identity. Focusing on one's sexual orientation would only delegitimize the complexities of those who identified as gay.

In just writing that, I understand what Ellen was hoping to convey. However, by merely avoiding politicizing her own queer identity, she could fit in... just like everyone else. I wholeheartedly understand that I am more than my gay self. I could give you a laundry list of the elements of my being that exceed that of my label as "gay." What troubles me, though, is the shunning of the queer label as a means of fitting in, as a method of connecting with a mainstream audience. That is not to say that Ellen should have become the spokesperson of gay rights, that she would be front and center in gay parades. What I am saying, by taking into account the write-up from Jennifer Reed is that, at some point, by carrying the burden of becoming one of the first, prominent gay figures in the media-- especially with the surge in media coverage pertaining to gays everywhere-- Ellen could have managed to saddle both sides of the spectrum, as a way to reach all audiences. Or, maybe, Reed puts it best on page 25: "Perhaps what television is teaching here is not the correct way to be a gay person, but that one can define that for oneself."

|

| But why aren't we talking about Antarctica's secrets? Was it the original Gossip Girl? |

Reed elaborates on this further when she discusses how Ellen manages to maneuver between queer, gay, to even postgay. These differences are spaced out through the duration of Ellen's two sitcoms of Ellen and The Ellen Show. In her first series, Ellen is living the life as an asexual woman, never being able to form a connection with another man. Reed highlights plot lines that indicate how Ellen is blossoming into a gay woman, and by portraying her as such, Ellen subverts the label of straight and gay. Thus, she is in this middle ground, a queer middle where she can subvert any and all expectations of her gender performance and/or sexual preference. Of course, due to the nature of the program, these are used for laughs, but Reed argues that this was a sweet spot for Ellen and for young gays across the country. The fact that Ellen was even hinting at her sexuality through the series, as well as her appearances on talk shows, indicated a drastic transition into our consumption of queer culture on mainstream television. Basically, this was huge!

"I'm gay." Two words that brought Ellen to the forefront of popular culture. The truth came out and the world needed to be ready to accept it. After winking at the camera for almost the entire fourth series of Ellen's run, she comes out as a gay woman. How cool is that? It is! Today, we may find it commonplace, and we still are problematizing coming out narratives as privileging heterosexuals' acceptance of one's queerness. But in 1997, wow. It makes me wish I had been there to witness it. As Reed dives into what this meant for gays everywhere, she also acknowledges that the series then took on an inadvertent responsibility. She notes, "If we think of television as a teacher, the question becomes who was being taught and what" (p. 17)? Essentially, Ellen being gay was a phenomenon. Okay, great, Where do we go from here? And what precisely can we take away from that.

Well, Ellen got cancelled. And shortly after, The Ellen Show premiered. This series was about a different woman with the same first name, and while she identified as gay, Ellen explicitly stated that she did not want the happenings in this show to be that of a gay woman. She argues that there is so much more to her personally than being a lesbian. Reed mentions here, that from moving from queer to gay, Ellen was now in a postgay phase of her cultural identity. In other words, this was a movement that hit on the idea that there are numerous facets to the queer identity. Focusing on one's sexual orientation would only delegitimize the complexities of those who identified as gay.

In just writing that, I understand what Ellen was hoping to convey. However, by merely avoiding politicizing her own queer identity, she could fit in... just like everyone else. I wholeheartedly understand that I am more than my gay self. I could give you a laundry list of the elements of my being that exceed that of my label as "gay." What troubles me, though, is the shunning of the queer label as a means of fitting in, as a method of connecting with a mainstream audience. That is not to say that Ellen should have become the spokesperson of gay rights, that she would be front and center in gay parades. What I am saying, by taking into account the write-up from Jennifer Reed is that, at some point, by carrying the burden of becoming one of the first, prominent gay figures in the media-- especially with the surge in media coverage pertaining to gays everywhere-- Ellen could have managed to saddle both sides of the spectrum, as a way to reach all audiences. Or, maybe, Reed puts it best on page 25: "Perhaps what television is teaching here is not the correct way to be a gay person, but that one can define that for oneself."

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)